In the last post I made the point that the America centered global system faces diminishing returns in it's attempts to expand that system. Another way of saying this is it has reached it's limits to growth. Any attempt to expand will cost more than the benefits that growth provides and eventually it will be forced to stop growing. I also said that it is a system which must grow in order to keep going. Once it stops growing then the system is in crisis. The economy today exhibits this growth crisis in so many ways. It's not too much to say all the indicators are screaming that the crisis is at heart one of growth. As of a few minutes ago, the screaming originated from the geopolitical realm in all sorts of ways, but the basis is this: The irresistible force of the growth imperative is slamming into a wall of resistance in the form of a natural wealth zero sum game.

This is the monster thesis of our times and what this humble blogger seeks to show. By studying this we can make sense of the inflection point.

Zero sum games are familiar enough. Every time you take your paycheck over to a buddy's house for a night of poker you are engaging in a zero sum game. The winner wins the exact sum that the loser loses. The size of the pot is limited by the size of the paychecks of all the buddies and does not shrink or grow. Pillage is another zero sum game. The pillaged lose an equal amount in wealth, misery, and death as the pillagers win in loot, good times, and status. The pot in this instance is limited by how much of the highest value stuff the pillagers can carry away.

Natural wealth is the useful pre-existing stuff that becomes valuable in money terms after it has been removed from the place it was found, usually the ground. In addition to this, natural wealth refers to everything nature does that makes life possible (services), such as plants exhaling oxygen, or grass growing to feed cows. So you could say natural wealth is all the "free" stuff before a dollar is ever used to drag it into the economy. All economic activity stems from this initial natural resource input. For many of the resources we humans depend on, the zero sum game is a one way flow from nature to the economy.

The economic zero sum game that I'm talking about involves the flow of available resources feeding into the global economy. The flow, or rate of flow, is time dependent. It is the amount of resources available on the market in a given period of time. As the word"flow" indicates, there is constancy to it. Over the entire period of the Industrial Age, resource flow has, on average, steadily increased.

Today the flow is in jeopardy. If it is not in fact slowing down it is more expensive to maintain that flow. American shale oil is the best example of a slowing flow rate. The cost of extraction is high and the depletion rate is fast compared to the past. The flow rate of shale oil puts the lie to the Saudi America myth. If it were truly like Saudi oil it would already have been used because Saudi oil is cheap and easy. Another sign of the slowing rate of flow is found in minerals such as copper. Copper miners are digging more and more rock out of the ground to extract less and less copper. This takes more energy to do and so is sensitive to the cost of oil as well. Putting both these trends for copper and oil together you have doubly more expensive resource inputs for economic use.

More expensive resources make it harder for economies to grow. Currently the world economy is not growing. The reason is that growth costs too much, as is evident in the swelling mound of digital debt money. Debt is a claim on the future. Money is created by issuing debt. A growing debt means people expect the future economy to be bigger. If the future economy is not bigger, or isn't even as big as people thought it would be, then a debt bubble forms. It might be useful to think of it as a money bubble with too much money chasing too few good goods. When expectations of a bigger future are not met, people can't pay back their debt, or their debt repayment takes all their money for reinvestment, and the economy doesn't grow. It can be effectively argued that the global economy has a thirty year old debt bubble. In 2008 it nearly popped.

A common analogy to make regarding the economy is to think of it as a pie. This pie is magical, though, because it grows. The pie growing magic spell's lease has ended and so now the pie has stopped growing. This, however, has not stopped people from trying to increase their own share of the pie. Some are successful and some are not. The successful ones, like the U.S., succeed at the expense of another, whose piece of pie shrinks. Think about the European Union, whose share of the pie is shrinking. The U.S. is taking a share of pie that used to belong to the European Union. The U.S. uses for it's currency the U.S. dollar, the world's reserve currency. Every single natural resource except tea (British Pound) is valued in and paid for using the U.S. dollar. The ability of the Fed to strengthen or weaken the dollar is a very big advantage for the U.S. economy, a power the EU does not really have. In a not-growing pie scenario, this matters a lot.

I found two good commentaries in the Automatic Earth's Debt Rattle news feed today to illustrate the zero sum nature of today's global economy. The first by the now familiar Ambrose Evans-Pritchard. Spanish wages have dropped to such a degree that it's car manufacturing plants are having a boom. These Spanish factories are taking jobs from other Eurozone economies whose wages are higher. Spain wins, the others lose. The second is from some wag writing for CNBC who at once describes the policy and political-economic global trade situation very well and demonstrates amply why you should never listen to what economists say. It's the political season here in America and so the trade deficit will at some point be brought up. It matters not at all whether anyone has any idea what to do about it let alone determine why it's like that to begin with. Everyone agrees it's bad. This Michael Ivanovitch talks about trade surplus/deficit in terms of "losing" such and such a percent of GDP, or "stripping" GDP from the rest of the world. Trade between nations, for all it's ballyhooed economic multiplier effect, is, on the balance sheet, a zero sum endeavor.

Ivanovitch seems to think that balancing trade is something likely to happen. Something must be done, after all. But the U.S. getting a trade balance with Germany and/or China runs into two major problems. The first is that these economies are successful because they are such big trade surpluses. The shaving off of GDP from other countries is how they have grown in the past, more so for China but still true for both. The second reason is that these two countries, as well as nearly every other country in the world, has stopped growing. Germany is being taken down with the rest of the EU due to it's trade surplus and China's boom has imploded, in no small part to the fact that Chinese consumers don't buy enough things. So who does the U.S. sell exports to?

The U.S. economy is the last man standing and it's debt-fueled consumption is what makes the world economy turn. But we humans are in a bind because we have an increasing scarcity of natural resources and a money system that wants to shed money. In other words, money wants to track the decline in the resource wealth it represents. This is the bubble in it's starkest sense. How we respond is anyone's guess but the zero sum games of gambling and pillaging resources would be a disastrous way to go. What we see around us is a dying economic system. It's logic has

reached it's furthest extent and is now so addled by debt and other constraints that it can

hardly continue. With QE we are effectively mining the future to maintain the present. At some point it will stop and it will be in crisis.

The nature of the crisis will be deflationary because people will be unable to

repay debt and so the debt (money) will disappear. When people see money disappear a powerful emotional response tends to follow, if I can be allowed a little understatement.

Some cheerful headlines for you:

The main problem with QE:

Financial Toxins

This one relates to the post "Russia and the Falling price of Oil". Might be a good one for Victoria "Fuck the EU" Nuland to read.

Arctic Sea Ice

More people getting energy wrong and losing money because of it.

Speculators

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Friday, October 24, 2014

Russia and the Falling Price of Oil

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has been on a role lately. In his latest piece in the Daily Telegraph he describes many working parts of the global oil/power configuration by way of the effect the falling price of oil has on geopolitics. What's more interesting than that is he gets into the ways in which the current situation is different from the past, which can be carried much further than I think he realizes. I'll explain that later. The virtue of his column is that he describes the current contest between Russia, Saudi Arabia and the U.S. very well.

Russia is in a desperate situation. It's oil export revenue is getting hammered by falling prices and this in turn is crushing the government's budget. Another key component is the economic sanctions preventing western technological know-how to add efficiency to the Russian oil industry. It also, incidentally, comes at a time when Russia's total oil production is in decline, an event which preceded the collapse of the Soviet Union. So Russia is at it's second peak in oil production in two decades and makes high oil prices even more vital. Pritchard highlights some major ways Russia under Putin has reached it's apex, and he very well could be right.

Before we, as Americans, collect our Super Bowl rings we should pause to consider the trade-offs. First of all, Saudi Arabia could be aiming it's pricing power at U.S. shale oil as well as at Russia in the hope of forcing bankruptcies on several American companies. Even if this is not the case, it's still likely that many American companies will crumple as victims of collateral damage. Here's a chart on the break even price of oil for American shale oil fields.

Roughly a third of these forty-five or so fields is running at a loss at current prices. Companies need profits, so about half lose money or break even when the price is at $80. Pritchard mentions that Russia is stress testing it's budget at $60 a barrel. Maybe it'll get there, maybe it won't, but that price wipes out at least half the fields on the chart above.

The second trade-off of falling oil prices to consider is the prospect of new failed states. Pritchard lists a few break even prices for governments, and some of these are solid candidates for failed state status. Nigeria, Oman, and Venezuela are in various states of chaos as it is. They also have very high price thresholds. Would these nations be more collateral damage? Whether friend or foe, how many failed states does it take to ignite global chaos? It looks to be another stress test of global stability as a consequence of the more narrow experiment of trying to take down the Putinator.

The third trade-off I see is between the benefit of a successful foreign policy of vanquishing enemies versus the costs. A lot of our contentions with Russia involve Ukraine. Ukraine is very poor and very corrupt. The U.S. seems to think it's important to keep it together as a unified country despite it's having a very large and restive Russian minority who wants to be a part of Russia. But American contentions with Russia go deeper than just Ukraine. The U.S., and more so, Saudi Arabia, also wants to help Syria in the effort to liberate itself from it's leader Bashar al-Assad. Assad, like his father, have made Syria a reliable ally of both Russia and the Soviet Union dating back to the 1960's. Syria is also allied with Iran, one of the Axis of Evil powers. Iran is a Russian ally as well, though I think it is a rather loose alliance. What I take from all of this is that the policy effort is to pluck allies from Russia and bring them into the American fold. All well and good, I suppose. It fits conventional statecraft all right.

But what does the U.S. really get out of the deal? It must be a lot. There must be a grand prize here that is worth having. Rather than speculate on what that could be (though I can come up with plenty of probable answers), it's enough to wonder whether there is actually a prize to be won. What are the chances that any of these states would be inclined to align it's interests with the U.S. and in effect become a client state? What are the chances that Syria just continues to be an extension of the chaos in Iraq after Assad is gone? What is the value of having a Ukraine which consists of two ethnic groups who hate each other? On the other hand, what is the real cost of letting Russia annex the Russian parts of Ukraine?

That's a lot of questions and none of them can really be answered. What the U.S. is facing is a mountain of trade-offs that don't exactly pay off. The more we try to maintain the global system, the more expensive it gets. A glance at the situation I think proves the point. The Arab Spring was really nothing of the sort. Nobody is more liberated now than they were before in those nations, like Egypt, that found some stability. But most of these nations are in upheaval now and the U.S. can't find any new regimes to fit the old model. Russia is set against us and, though the U.S. may win the battle, it could very easily resemble losing.

At the end of his commentary, Pritchard talks about the "chance" that Russia has had to join the community of free nations. The West "eagerly" tried to help, after all. I think this is a pile of hoo-ha. Pritchard could have straightened out his thinking if he'd only reread one of his earlier paragraphs, the one in which he mentions the "imperial" might of the American financial system. Without realizing it, I suspect, he hit on the head the nail of why Putin was able to rise to power and was unwilling to follow the American Dream. The real story goes more like this: After the fall of the Soviet Union, instead of eager helpers, as Pritchard claims, the Americans sent in the vultures. The shock therapy treatment prescribed to jolt Russia's economy into a, what, stupor? Because that's what someone falls into after shock therapy. And that's what happened to Russia, particularly President Boris Yeltsin, who was a weak, confused leader who, with the "help" of our economic prescriptions, based on the Washington Consensus theory of helping nations, enabled the rise and domination of the Russian oligarchs. It's not what we thought would happen, but that is what happened. Pritchard likes his story because he is a financial journalist.

Putin came along and was sufficiently strong to tame the oligarchs. He's polished, he's disciplined, and he knows how to wield power. Plus, he's a nationalist, and could take advantage and gain popular support by making Russia stand up again as a strong nation after the humiliation it had experienced at the hands of the West. That's what nationalists seek to do and the U.S. doesn't seem to understand this. This form of "help" was seen as a national humiliation by Russians.

This is not an uncommon theme. Latin America has a similar perception as evidenced by a lively Marxism throughout the region. Any country which has suffered from unregulated capital flows such as SE Asia, Argentina, and the like, wishing to increase it's own share of the pie, experiences a lack of control and disadvantaged positions under free trade and open markets. The reason is that the Washington Consensus of free trade and open markets is an imperial system. Americans don't like to think of it this way, but if you consider the results; more outflow of wealth to the U.S. than inflow to these various economies and an unpayable debt load imposed on them by western banks, then the system starts to look kind of imperial. Free Market ideology is in essence a glossy rationalization for a wealth transfer system. By contrast, those nations who didn't participate in the Washington Consensus model, like Japan, China, South Korea, are the richest and most successful. Russia resisted what was an attempt by the U.S. to straddle it with debt and an unfavorable trade relationship. Putin's not stupid. He saw Russia caught in the free trade and open market trap and chose to protect his markets.

Russia, though, didn't play it's hand very well, economically speaking. It's become under Putin a petrol-dictatorship, or, more accurately, a resource dictatorship with expansionary ambitions. It worked for a while but now it's struggling in a deflationary global economy and possibly faces another collapse. But a collapse doesn't mean Putin won't still be the leader. Russia has fall back positions that are built in to the culture that are durable but Russia as a whole will be weaker.

So what is the prize? The way I see it, the prize is growth of the America centered global economic system. It is a system which must grow so opportunities for growth must always be seized. I suspect that lurking in the heart of the American security and corporate elite is a desire for revenge. Russia is the one that got away, and Vladimir Putin took it from us. Rather than a mineral and energy rich client state with a large population the U.S. got a powerful and antagonistic semi-rogue state. Such are the complications of geopolitics.

I read all of this as another aspect of diminishing returns. Our choices now come with higher price tags. The cost of expanding territory and markets to fill the needs of the system is greater than the benefit. What I've outlined here is a situation where the U.S. has only paltry gains at high cost. Maybe someday average Ukrainian households will fill their two car garages with Teslas and John Deer lawnmowers and thereby achieve consumer paradise. Or something else entirely will happen. I'm banking on the something else.

Russia is in a desperate situation. It's oil export revenue is getting hammered by falling prices and this in turn is crushing the government's budget. Another key component is the economic sanctions preventing western technological know-how to add efficiency to the Russian oil industry. It also, incidentally, comes at a time when Russia's total oil production is in decline, an event which preceded the collapse of the Soviet Union. So Russia is at it's second peak in oil production in two decades and makes high oil prices even more vital. Pritchard highlights some major ways Russia under Putin has reached it's apex, and he very well could be right.

Before we, as Americans, collect our Super Bowl rings we should pause to consider the trade-offs. First of all, Saudi Arabia could be aiming it's pricing power at U.S. shale oil as well as at Russia in the hope of forcing bankruptcies on several American companies. Even if this is not the case, it's still likely that many American companies will crumple as victims of collateral damage. Here's a chart on the break even price of oil for American shale oil fields.

Roughly a third of these forty-five or so fields is running at a loss at current prices. Companies need profits, so about half lose money or break even when the price is at $80. Pritchard mentions that Russia is stress testing it's budget at $60 a barrel. Maybe it'll get there, maybe it won't, but that price wipes out at least half the fields on the chart above.

The second trade-off of falling oil prices to consider is the prospect of new failed states. Pritchard lists a few break even prices for governments, and some of these are solid candidates for failed state status. Nigeria, Oman, and Venezuela are in various states of chaos as it is. They also have very high price thresholds. Would these nations be more collateral damage? Whether friend or foe, how many failed states does it take to ignite global chaos? It looks to be another stress test of global stability as a consequence of the more narrow experiment of trying to take down the Putinator.

The third trade-off I see is between the benefit of a successful foreign policy of vanquishing enemies versus the costs. A lot of our contentions with Russia involve Ukraine. Ukraine is very poor and very corrupt. The U.S. seems to think it's important to keep it together as a unified country despite it's having a very large and restive Russian minority who wants to be a part of Russia. But American contentions with Russia go deeper than just Ukraine. The U.S., and more so, Saudi Arabia, also wants to help Syria in the effort to liberate itself from it's leader Bashar al-Assad. Assad, like his father, have made Syria a reliable ally of both Russia and the Soviet Union dating back to the 1960's. Syria is also allied with Iran, one of the Axis of Evil powers. Iran is a Russian ally as well, though I think it is a rather loose alliance. What I take from all of this is that the policy effort is to pluck allies from Russia and bring them into the American fold. All well and good, I suppose. It fits conventional statecraft all right.

But what does the U.S. really get out of the deal? It must be a lot. There must be a grand prize here that is worth having. Rather than speculate on what that could be (though I can come up with plenty of probable answers), it's enough to wonder whether there is actually a prize to be won. What are the chances that any of these states would be inclined to align it's interests with the U.S. and in effect become a client state? What are the chances that Syria just continues to be an extension of the chaos in Iraq after Assad is gone? What is the value of having a Ukraine which consists of two ethnic groups who hate each other? On the other hand, what is the real cost of letting Russia annex the Russian parts of Ukraine?

That's a lot of questions and none of them can really be answered. What the U.S. is facing is a mountain of trade-offs that don't exactly pay off. The more we try to maintain the global system, the more expensive it gets. A glance at the situation I think proves the point. The Arab Spring was really nothing of the sort. Nobody is more liberated now than they were before in those nations, like Egypt, that found some stability. But most of these nations are in upheaval now and the U.S. can't find any new regimes to fit the old model. Russia is set against us and, though the U.S. may win the battle, it could very easily resemble losing.

At the end of his commentary, Pritchard talks about the "chance" that Russia has had to join the community of free nations. The West "eagerly" tried to help, after all. I think this is a pile of hoo-ha. Pritchard could have straightened out his thinking if he'd only reread one of his earlier paragraphs, the one in which he mentions the "imperial" might of the American financial system. Without realizing it, I suspect, he hit on the head the nail of why Putin was able to rise to power and was unwilling to follow the American Dream. The real story goes more like this: After the fall of the Soviet Union, instead of eager helpers, as Pritchard claims, the Americans sent in the vultures. The shock therapy treatment prescribed to jolt Russia's economy into a, what, stupor? Because that's what someone falls into after shock therapy. And that's what happened to Russia, particularly President Boris Yeltsin, who was a weak, confused leader who, with the "help" of our economic prescriptions, based on the Washington Consensus theory of helping nations, enabled the rise and domination of the Russian oligarchs. It's not what we thought would happen, but that is what happened. Pritchard likes his story because he is a financial journalist.

Putin came along and was sufficiently strong to tame the oligarchs. He's polished, he's disciplined, and he knows how to wield power. Plus, he's a nationalist, and could take advantage and gain popular support by making Russia stand up again as a strong nation after the humiliation it had experienced at the hands of the West. That's what nationalists seek to do and the U.S. doesn't seem to understand this. This form of "help" was seen as a national humiliation by Russians.

This is not an uncommon theme. Latin America has a similar perception as evidenced by a lively Marxism throughout the region. Any country which has suffered from unregulated capital flows such as SE Asia, Argentina, and the like, wishing to increase it's own share of the pie, experiences a lack of control and disadvantaged positions under free trade and open markets. The reason is that the Washington Consensus of free trade and open markets is an imperial system. Americans don't like to think of it this way, but if you consider the results; more outflow of wealth to the U.S. than inflow to these various economies and an unpayable debt load imposed on them by western banks, then the system starts to look kind of imperial. Free Market ideology is in essence a glossy rationalization for a wealth transfer system. By contrast, those nations who didn't participate in the Washington Consensus model, like Japan, China, South Korea, are the richest and most successful. Russia resisted what was an attempt by the U.S. to straddle it with debt and an unfavorable trade relationship. Putin's not stupid. He saw Russia caught in the free trade and open market trap and chose to protect his markets.

Russia, though, didn't play it's hand very well, economically speaking. It's become under Putin a petrol-dictatorship, or, more accurately, a resource dictatorship with expansionary ambitions. It worked for a while but now it's struggling in a deflationary global economy and possibly faces another collapse. But a collapse doesn't mean Putin won't still be the leader. Russia has fall back positions that are built in to the culture that are durable but Russia as a whole will be weaker.

So what is the prize? The way I see it, the prize is growth of the America centered global economic system. It is a system which must grow so opportunities for growth must always be seized. I suspect that lurking in the heart of the American security and corporate elite is a desire for revenge. Russia is the one that got away, and Vladimir Putin took it from us. Rather than a mineral and energy rich client state with a large population the U.S. got a powerful and antagonistic semi-rogue state. Such are the complications of geopolitics.

I read all of this as another aspect of diminishing returns. Our choices now come with higher price tags. The cost of expanding territory and markets to fill the needs of the system is greater than the benefit. What I've outlined here is a situation where the U.S. has only paltry gains at high cost. Maybe someday average Ukrainian households will fill their two car garages with Teslas and John Deer lawnmowers and thereby achieve consumer paradise. Or something else entirely will happen. I'm banking on the something else.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Energy and Complex Systems

In the last post I made a partial case for visible, measurable signs of diminishing returns on economic activity as an effect of rising energy costs. The rising cost of energy is an effect of rising costs of getting that energy, which reduces the return on investments and reduces the overall affordable energy available to the system. I used the example of oil because it is the most important source of energy and what happens with oil reverberates throughout the entire system. The greatest and most fundamental expression of the impact of rising oil costs is seen in the debt load of the global economy.

I pay attention to, and try to understand, what happens in the economy because it is through the economy that we will experience this loss of available energy. Energy very closely resembles God; it is inside, outside, and moves through everything, without it nothing can be done, it has bafflingly mysterious properties, and it follows it's own laws and imposes them on others. The amount and the quality of it's blessing determines to a large extent how rich our lives can be. The land of milk and honey is a land rich in available energy and societal prosperity is determined by how much energy can be harvested and how wisely it is used. It is both useful and enlightening to view the economy as an energy system within and dependent on a larger energy system.

You could call this a natural view of the economy. Energy represents the furthest reducible form the study of systems can take, whether it's a natural system or a human system. The laws of energy determine the parameters and the form of a system. If you apply this to the history of economic systems all sorts of insights are revealed. For example, the industrial revolution is commonly characterized as a technological revolution, as a leap in human understanding of the laws of nature which enabled humans to use machines to further economic prosperity. This is more or less accurate. There is no question that human ingenuity accomplished this part of it. But it is still only part of the story. An economist would say that advances in Enlightenment Age economic thinkers like Adam Smith and David Ricardo spurred the march of progress. Still accurate, but insufficient. Call it a second order factor. For a fuller, more complete explanation, from a systems perspective the Industrial Revolution was primarily an energy revolution.

Modern Economics was born out of the same societal milieu as was the Industrial Revolution. At the time of Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations" the nascent industrial revolution had just begun. Smith described what would become the mainstay of industrial processes like the division of labor and the efficiencies that were gained from it, but the machine element preceded it slightly and sprang from the energy revolution.

The idea of the machine had been around a long time before the industrial revolution. Leonardo da Vinci created designs for machines. The Romans had what you could call "industrial" scale pottery factories, but these early machines and techniques relied on some combination of wind, water, human, and animal power, and heat energy came mostly from wood and peat. What characterizes the industrial revolution, and the reason I think it is (mis?)characterized as a "revolution" and not as an "evolution", is the energy density of coal compared to that of wind, water, peat, or wood and the other sources that came before. It was only through the introduction of coal energy to do work by way of machines did the real industrial revolution as we've come to understand it take off. The reason is simple: The energy density of coal provided a sufficient surplus of energy to enable a long and bountiful quest for efficiencies that in turn translated into capital. Capital is surplus money. Capitalism then can be understood as having spawned from a surplus of available energy beginning in the late 18th century.

It's important to trace the beginning of the modern era to that of energy surplus. The modern era is defined by the abundance of material well being and the power at our disposal. We marvel (and shudder) at the lives led by our ancestors who farmed, labored, and traveled in ways we have little patience for today. It was a difficult life compared to ours because the amount of work done was accomplished by less energy dense means. A human does one/tenth the labor of a horse. A horse does a hundredth of the amount of work of a small tractor. Because of this tractor, fewer humans are needed to produce food and they can merrily leave the farm and go to the city, where there is a job as a factory worker, or as a novelist chronicling the crappy lives of factory workers, or, ultimately, as a Deputy Assistant Regional Manager for Personal Finance Products waiting for them. This is the point at which societal complexity enters the room.

The number and array of job titles is a good measure of the complexity of a human system. Complexity is seen in the number of different roles people can have, and in the number of institutional components and strata the system supports. A hunter/gatherer society is simple because you can count all the occupations in the name. Hunting and gathering lifestyles do not afford much, if any, surplus, and surplus is undesirable because there is nothing to do with it beyond gaining weight or enticing a mate. In today's world, the U.S government serves as an excellent and much talked about example of a complex human system. An orders of magnitude larger system is the global economy. This is the single largest system ever constructed in human history. The evolution of this system is indeed an evolution, but it's evolution has been fed by an increase in the amount of energy available to it on average about two percent every year for two centuries now. The two percent increase in annual energy input into the system accounts for the increase in it's complexity. For reasons I've already mentioned, it now suffers from diminishing returns and faces a reduced flow of energy into it.

Viewing the Industrial Revolution as an energy revolution adds a necessary perspective. It allows a deeper appreciation for the ways nature bounds us and our choices. This is not a squishy-headed assertion. Mother Nature isn't always a sweet, nurturing caregiver. She can just as easily put us over her knee and give us a good whoopin'. What's more, she wouldn't even feel guilty about it.

Further information on this subject, and a source of some of my information and thinking about it is found in the video below. Nate Hagens is a wonderfully broad thinker and endeavors to make a single omni-inclusive one hour powerpoint presentation some day. He fails here and goes 1:10:00 roughly. The questions at the end go twenty more minutes but it's not necessary to listen.

For a general systems perspective a good podcast interview with David Korowicz from Feasta (pr. fasta) works well. Korowicz is a physicist and studies human systems. In this he talks about how systems can collapse and uses various real-world crises to illustrate. He is interviewed by Tom O'Brien from From Alpha to Omega.

http://fromalpha2omega.podomatic.com/entry/2012-04-17T16_29_23-07_00

I pay attention to, and try to understand, what happens in the economy because it is through the economy that we will experience this loss of available energy. Energy very closely resembles God; it is inside, outside, and moves through everything, without it nothing can be done, it has bafflingly mysterious properties, and it follows it's own laws and imposes them on others. The amount and the quality of it's blessing determines to a large extent how rich our lives can be. The land of milk and honey is a land rich in available energy and societal prosperity is determined by how much energy can be harvested and how wisely it is used. It is both useful and enlightening to view the economy as an energy system within and dependent on a larger energy system.

You could call this a natural view of the economy. Energy represents the furthest reducible form the study of systems can take, whether it's a natural system or a human system. The laws of energy determine the parameters and the form of a system. If you apply this to the history of economic systems all sorts of insights are revealed. For example, the industrial revolution is commonly characterized as a technological revolution, as a leap in human understanding of the laws of nature which enabled humans to use machines to further economic prosperity. This is more or less accurate. There is no question that human ingenuity accomplished this part of it. But it is still only part of the story. An economist would say that advances in Enlightenment Age economic thinkers like Adam Smith and David Ricardo spurred the march of progress. Still accurate, but insufficient. Call it a second order factor. For a fuller, more complete explanation, from a systems perspective the Industrial Revolution was primarily an energy revolution.

Modern Economics was born out of the same societal milieu as was the Industrial Revolution. At the time of Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations" the nascent industrial revolution had just begun. Smith described what would become the mainstay of industrial processes like the division of labor and the efficiencies that were gained from it, but the machine element preceded it slightly and sprang from the energy revolution.

The idea of the machine had been around a long time before the industrial revolution. Leonardo da Vinci created designs for machines. The Romans had what you could call "industrial" scale pottery factories, but these early machines and techniques relied on some combination of wind, water, human, and animal power, and heat energy came mostly from wood and peat. What characterizes the industrial revolution, and the reason I think it is (mis?)characterized as a "revolution" and not as an "evolution", is the energy density of coal compared to that of wind, water, peat, or wood and the other sources that came before. It was only through the introduction of coal energy to do work by way of machines did the real industrial revolution as we've come to understand it take off. The reason is simple: The energy density of coal provided a sufficient surplus of energy to enable a long and bountiful quest for efficiencies that in turn translated into capital. Capital is surplus money. Capitalism then can be understood as having spawned from a surplus of available energy beginning in the late 18th century.

It's important to trace the beginning of the modern era to that of energy surplus. The modern era is defined by the abundance of material well being and the power at our disposal. We marvel (and shudder) at the lives led by our ancestors who farmed, labored, and traveled in ways we have little patience for today. It was a difficult life compared to ours because the amount of work done was accomplished by less energy dense means. A human does one/tenth the labor of a horse. A horse does a hundredth of the amount of work of a small tractor. Because of this tractor, fewer humans are needed to produce food and they can merrily leave the farm and go to the city, where there is a job as a factory worker, or as a novelist chronicling the crappy lives of factory workers, or, ultimately, as a Deputy Assistant Regional Manager for Personal Finance Products waiting for them. This is the point at which societal complexity enters the room.

The number and array of job titles is a good measure of the complexity of a human system. Complexity is seen in the number of different roles people can have, and in the number of institutional components and strata the system supports. A hunter/gatherer society is simple because you can count all the occupations in the name. Hunting and gathering lifestyles do not afford much, if any, surplus, and surplus is undesirable because there is nothing to do with it beyond gaining weight or enticing a mate. In today's world, the U.S government serves as an excellent and much talked about example of a complex human system. An orders of magnitude larger system is the global economy. This is the single largest system ever constructed in human history. The evolution of this system is indeed an evolution, but it's evolution has been fed by an increase in the amount of energy available to it on average about two percent every year for two centuries now. The two percent increase in annual energy input into the system accounts for the increase in it's complexity. For reasons I've already mentioned, it now suffers from diminishing returns and faces a reduced flow of energy into it.

Viewing the Industrial Revolution as an energy revolution adds a necessary perspective. It allows a deeper appreciation for the ways nature bounds us and our choices. This is not a squishy-headed assertion. Mother Nature isn't always a sweet, nurturing caregiver. She can just as easily put us over her knee and give us a good whoopin'. What's more, she wouldn't even feel guilty about it.

Further information on this subject, and a source of some of my information and thinking about it is found in the video below. Nate Hagens is a wonderfully broad thinker and endeavors to make a single omni-inclusive one hour powerpoint presentation some day. He fails here and goes 1:10:00 roughly. The questions at the end go twenty more minutes but it's not necessary to listen.

For a general systems perspective a good podcast interview with David Korowicz from Feasta (pr. fasta) works well. Korowicz is a physicist and studies human systems. In this he talks about how systems can collapse and uses various real-world crises to illustrate. He is interviewed by Tom O'Brien from From Alpha to Omega.

http://fromalpha2omega.podomatic.com/entry/2012-04-17T16_29_23-07_00

Friday, October 17, 2014

Energy, Debt, and Signs of Decline

In the URL of this blog resides the word "decomplexity". It is not a real word, but I invented it out of the wish to have a single unused address for the blog that would be, or could be, made sensible. Decomplexity refers to a future state society, or civilization, will inevitably reach given natural resource constraints to it's continued existence. I say "inevitable" because I mean inevitable. By saying that, however, doesn't mean the power to achieve or to choose certain outcomes isn't possible, but we have to choose carefully among these limited options. Further investment in complexity further constrains our options over time, so choices made now have huge implications later.

In any given system, the level of complexity of that system is determined by the amount of available energy to that system. An ecosystem has a high or low level of biodiversity based on the energy flows going through it. The same holds true for complex machines, organisms, or socio-economic organizations. A cell phone is a complex machine. In itself it uses relatively little energy to operate, but is useless without a system of server farms, cell phone towers, manufacturing plants, and millions of consumers to pay into the system. This system which enables a cell phone to function uses more energy than the system it replaced, namely the old land line phone system. The increase of energy translates into greater GDP for the economy.

The system on which cell phones depend represents a greater complexity for society as a whole. Technology as a whole adds complexity and by extension adds costs. Technology adds efficiency, but efficiency itself comes at a cost. The only way to overcome these costs is by adding energy to the system, namely the economic system, which is the way the system is measured. By following the flows of money you can get a picture of the systems complexity.

In 1987, to little fanfare, a book called "The Collapse of Complex Societies" was published. It was written by the archeologist Joseph Tainter pursuing the age old question of why civilizations collapse. He was looking for a cause which unified all cases of civilization collapse seeing the ongoing theories at the time as inadequate for explaining every case. He goes through an exhaustive review of all the theories at the beginning of the book and provides counter examples to disprove a multitude of theories. What he found to unify every instance of collapse was what looked like the economics "Law of Diminishing Returns".

The diminishing returns he saw was in the response to crises of various sorts that a civilization confronted by adding complexity to it's systems. This applied no matter the scale of the civilization. From Rome to the Chacoan of the American southwest, a tiny society numbering maybe ten thousand at it's peak, the story was the same. He found in the archeological record the course of crises and the responses to them a pattern of adding more complex structures, which made things more efficient, but also added greater energetic and maintenance costs. At this point, things should start to sound familiar. Eventually the costs outweighed the benefits, which made the society less resilient to further crises and susceptible to collapse.

John Michael Greer has a spin-off theory of "Catabolic" collapse which describes the forces that eat away at the resilience of the society on it's way down.

How does this apply to the current situation of global civilization? What signs are there of diminishing returns? I will look at the trends in energy and debt to make my case.

We are getting diminishing returns on the amount of debt needed to get a unit of GDP growth. You can see how the crisis of 2008 could be devastating. If the debt line drops you are in a deflationary trap.

Now, in conventional economic theory, the price is the product of supply and demand. This holds true for oil even with today's high prices. A rising price means demand is outstripping supply and the market should, according to theory, respond with greater supply to the market. But this is not happening, as this chart makes clear.

This next chart shows the history of real and nominal oil prices over the entire history of the oil industry.

Compare this to the first chart and notice that, in the first chart, the debt line began to diverge from the GDP line in the early 1970's. This third chart shows that the price of oil got all wonky at the same time. The reason why this happened doesn't matter, the only point necessary to make is that these two events went hand in hand.

And now a look at total debt as a percentage of GDP.

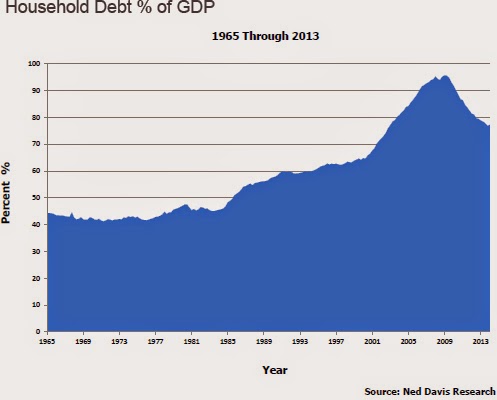

Total debt includes both public (government) debt and private (household and corporate) debt. Most of this debt is not from government. It is from the private sector. Government debt as a percentage of GDP is on the rise now because private sector debt, mainly household, is falling. The reason the Federal Reserve has been pushing down interest rates is to spur further borrowing by the private sector. Here's a picture of household debt.

This is the profile of household deleveraging (paying down debt). It is the same process that characterized the Great Depression.

This collection of graphs tells the story of diminishing returns. Another way to put it is that the costs of maintaining and growing the system is outstripping the benefits. Our answer to these trends has been to increase complexity and efficiency, through debt accumulation, in the hope that the economy will "break out" of it's doldrums and start another virtuous cycle of growth. Growth in the economy is imperative to service the outstanding debt. Global growth rates have been flat and we appear to be entering a new crisis period because of the pressure to delever. How should we respond? Should we add more debt to try to spur more growth? The answer is not as straightforward as it seems.

Before anything major gets decided on people should at least acknowledge our predicament, but we're far from doing that. Accepting the end of growth story and all of it's implications is indeed depressing and/or frightening and most everyone resists even considering the possibility. But that has to be gotten through when the time comes to respond in an intelligent and thoughtful way when this system of economy chugs to it's final failure. I don't know when that will be and nobody can say exactly when. But given the condition of the world right now, it's possible to see the shape that failure will take, and it looks like a prolonged economic depression that we can only adapt to and make the best of. But to expect economic growth to return in any meaningful way is pure folly.

Today's links on deflation:

Bond Markets Respond to Deflation Fears

The Feds response seems to be:

Fed

Our friends at the House of Saud don't appreciate our shale oil "revolution":

Loyal Allies

In any given system, the level of complexity of that system is determined by the amount of available energy to that system. An ecosystem has a high or low level of biodiversity based on the energy flows going through it. The same holds true for complex machines, organisms, or socio-economic organizations. A cell phone is a complex machine. In itself it uses relatively little energy to operate, but is useless without a system of server farms, cell phone towers, manufacturing plants, and millions of consumers to pay into the system. This system which enables a cell phone to function uses more energy than the system it replaced, namely the old land line phone system. The increase of energy translates into greater GDP for the economy.

The system on which cell phones depend represents a greater complexity for society as a whole. Technology as a whole adds complexity and by extension adds costs. Technology adds efficiency, but efficiency itself comes at a cost. The only way to overcome these costs is by adding energy to the system, namely the economic system, which is the way the system is measured. By following the flows of money you can get a picture of the systems complexity.

In 1987, to little fanfare, a book called "The Collapse of Complex Societies" was published. It was written by the archeologist Joseph Tainter pursuing the age old question of why civilizations collapse. He was looking for a cause which unified all cases of civilization collapse seeing the ongoing theories at the time as inadequate for explaining every case. He goes through an exhaustive review of all the theories at the beginning of the book and provides counter examples to disprove a multitude of theories. What he found to unify every instance of collapse was what looked like the economics "Law of Diminishing Returns".

The diminishing returns he saw was in the response to crises of various sorts that a civilization confronted by adding complexity to it's systems. This applied no matter the scale of the civilization. From Rome to the Chacoan of the American southwest, a tiny society numbering maybe ten thousand at it's peak, the story was the same. He found in the archeological record the course of crises and the responses to them a pattern of adding more complex structures, which made things more efficient, but also added greater energetic and maintenance costs. At this point, things should start to sound familiar. Eventually the costs outweighed the benefits, which made the society less resilient to further crises and susceptible to collapse.

John Michael Greer has a spin-off theory of "Catabolic" collapse which describes the forces that eat away at the resilience of the society on it's way down.

How does this apply to the current situation of global civilization? What signs are there of diminishing returns? I will look at the trends in energy and debt to make my case.

We are getting diminishing returns on the amount of debt needed to get a unit of GDP growth. You can see how the crisis of 2008 could be devastating. If the debt line drops you are in a deflationary trap.

Now, in conventional economic theory, the price is the product of supply and demand. This holds true for oil even with today's high prices. A rising price means demand is outstripping supply and the market should, according to theory, respond with greater supply to the market. But this is not happening, as this chart makes clear.

This next chart shows the history of real and nominal oil prices over the entire history of the oil industry.

Compare this to the first chart and notice that, in the first chart, the debt line began to diverge from the GDP line in the early 1970's. This third chart shows that the price of oil got all wonky at the same time. The reason why this happened doesn't matter, the only point necessary to make is that these two events went hand in hand.

And now a look at total debt as a percentage of GDP.

Total debt includes both public (government) debt and private (household and corporate) debt. Most of this debt is not from government. It is from the private sector. Government debt as a percentage of GDP is on the rise now because private sector debt, mainly household, is falling. The reason the Federal Reserve has been pushing down interest rates is to spur further borrowing by the private sector. Here's a picture of household debt.

This is the profile of household deleveraging (paying down debt). It is the same process that characterized the Great Depression.

This collection of graphs tells the story of diminishing returns. Another way to put it is that the costs of maintaining and growing the system is outstripping the benefits. Our answer to these trends has been to increase complexity and efficiency, through debt accumulation, in the hope that the economy will "break out" of it's doldrums and start another virtuous cycle of growth. Growth in the economy is imperative to service the outstanding debt. Global growth rates have been flat and we appear to be entering a new crisis period because of the pressure to delever. How should we respond? Should we add more debt to try to spur more growth? The answer is not as straightforward as it seems.

Before anything major gets decided on people should at least acknowledge our predicament, but we're far from doing that. Accepting the end of growth story and all of it's implications is indeed depressing and/or frightening and most everyone resists even considering the possibility. But that has to be gotten through when the time comes to respond in an intelligent and thoughtful way when this system of economy chugs to it's final failure. I don't know when that will be and nobody can say exactly when. But given the condition of the world right now, it's possible to see the shape that failure will take, and it looks like a prolonged economic depression that we can only adapt to and make the best of. But to expect economic growth to return in any meaningful way is pure folly.

Today's links on deflation:

Bond Markets Respond to Deflation Fears

The Feds response seems to be:

Fed

Our friends at the House of Saud don't appreciate our shale oil "revolution":

Loyal Allies

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

Paul Krugman and the Delusion of Economists

Delusion is a big word. It's the kind of word that lends itself to abuse when one is seeking to abuse one's opponents. In the case of the construct of economic thought, it's use is warranted given the narrow field of it's vision on the operating system of the universe. Economists have the ears of national leaders all over the world, their academics represent an enormous chunk of the resources which go into the study of phenomena that make up society, and they have an inordinately large voice in the modern world's mythos. The accuracy and viability of their art/science is a mental foundation we've all come to depend on.

If economists have something wrong with their conceptualization of the universe, it follows that we all have a stake in the consequences. Especially if it's at the foundation of economic activity, where the economy intersects with the natural world. When we pull stuff out of the ground, turn it into something, which is then represented by money, used by someone, and thrown away, we have the phenomena of interest to economists. When there is a problem at the beginning of this chain, problems occur all along the rest of the chain. Call this the physical input stage, the point at which all economic activity begins. What happens before that? Who can say? It's just stuff that's there.

Physical scientists actually have something to say about it. I've said before in so many words that economists inhabit a small space, an isolated realm that is prominently placed is the social hierarchy. Naturally they try to defend that territory. A recent dust-up between Paul Krugman and one of my Dark Green Tribal members Richard Heinberg serves as a great illustration of the point I'm making. The dust-up reveals Krugman to be an economist willing to defend his territory. By doing so he also reveals how dismissive he is to arguments he doesn't understand or fit his models. He is firmly entrenched in the tower of his own ego.

In a blog post from September 18, Krugman calls out the Post Carbon Institute on the impossibility of infinite, or even further, economic growth. In the same breath he couples the Post Carbon Institute with the Koch Brothers and other climate change deniers because of PCI's position that economic growth is incompatible with either combating climate change or living sustainably on the planet. The ever thoughtful Heinberg responded to him with this missive on his own website, pointing out the many ways Krugman was wrong.

Krugman, in another post, reiterated his assertion that the "anti-growth" movement was in an "unholy alliance" with right wing climate deniers. The blog post was in response to this article from Bloomberg attacking economists on the limits to growth issue. Heinberg responded with what I think is the best summation of why economies will stop growing because of the limits to the natural resource base and energetic limits.

Paul Krugman and the Limits to Hubris

I'm a little surprised by how sloppy Krugman's writing is on his blog, especially compared to Heinberg. I haven't read Krugman's blog for a while and it's been at least five years since I read "Conscience of a Liberal" but it feels more like a screed than anything else. But anyway.

The back and forth since the original "Limits to Growth" was published in 1972 has been between economists and environmentalists and the cost has come mainly at the expense of the environmentalist movement. The general view is that the economists won against the environmentalists because the scary predictions made at the time by environmentalists were proven wrong. But that was the public relations and policy side of it, which environmentalists definitely lost. But the "Limits to Growth" projections were over a much larger time frame than people acknowledge. The Club of Rome study did not say the limits would be reached in the seventies, but sometime after about 2030. Economics and financial markets don't think far into the future because of the nature of what they study. To use the weather analogy, the conditions on which they base their predictions and analysis change constantly. You can say general things about it, but the "weather" of the economy is in constant flux. A physicist looking at the economy is more analogous to how a climatologist looks at the weather. Climatology is not the weather. It is the study of the conditions in which the weather plays out. Krugman is a weatherman.

By attacking physical scientists Krugman shows his territorial markings. He is unwilling to view his own position in a context that is greater than the one he normally deals in. To use Krugman's own logic against him, he is siding with creationists and climate deniers by attacking the knowledge and insights of the physical sciences. Now that he is in bed with these folks, I guess we can fix our attitude against anything he says. Or, we can be reasonable, which is a very scientific thing to be.

Now, some headlines meant to terrify.

BIS warns on "violent" reversal of global markets

All is not well in the Kingdom

A frighteningly real "exogenous" event.

If economists have something wrong with their conceptualization of the universe, it follows that we all have a stake in the consequences. Especially if it's at the foundation of economic activity, where the economy intersects with the natural world. When we pull stuff out of the ground, turn it into something, which is then represented by money, used by someone, and thrown away, we have the phenomena of interest to economists. When there is a problem at the beginning of this chain, problems occur all along the rest of the chain. Call this the physical input stage, the point at which all economic activity begins. What happens before that? Who can say? It's just stuff that's there.

Physical scientists actually have something to say about it. I've said before in so many words that economists inhabit a small space, an isolated realm that is prominently placed is the social hierarchy. Naturally they try to defend that territory. A recent dust-up between Paul Krugman and one of my Dark Green Tribal members Richard Heinberg serves as a great illustration of the point I'm making. The dust-up reveals Krugman to be an economist willing to defend his territory. By doing so he also reveals how dismissive he is to arguments he doesn't understand or fit his models. He is firmly entrenched in the tower of his own ego.

In a blog post from September 18, Krugman calls out the Post Carbon Institute on the impossibility of infinite, or even further, economic growth. In the same breath he couples the Post Carbon Institute with the Koch Brothers and other climate change deniers because of PCI's position that economic growth is incompatible with either combating climate change or living sustainably on the planet. The ever thoughtful Heinberg responded to him with this missive on his own website, pointing out the many ways Krugman was wrong.

Krugman, in another post, reiterated his assertion that the "anti-growth" movement was in an "unholy alliance" with right wing climate deniers. The blog post was in response to this article from Bloomberg attacking economists on the limits to growth issue. Heinberg responded with what I think is the best summation of why economies will stop growing because of the limits to the natural resource base and energetic limits.

Paul Krugman and the Limits to Hubris

I'm a little surprised by how sloppy Krugman's writing is on his blog, especially compared to Heinberg. I haven't read Krugman's blog for a while and it's been at least five years since I read "Conscience of a Liberal" but it feels more like a screed than anything else. But anyway.

The back and forth since the original "Limits to Growth" was published in 1972 has been between economists and environmentalists and the cost has come mainly at the expense of the environmentalist movement. The general view is that the economists won against the environmentalists because the scary predictions made at the time by environmentalists were proven wrong. But that was the public relations and policy side of it, which environmentalists definitely lost. But the "Limits to Growth" projections were over a much larger time frame than people acknowledge. The Club of Rome study did not say the limits would be reached in the seventies, but sometime after about 2030. Economics and financial markets don't think far into the future because of the nature of what they study. To use the weather analogy, the conditions on which they base their predictions and analysis change constantly. You can say general things about it, but the "weather" of the economy is in constant flux. A physicist looking at the economy is more analogous to how a climatologist looks at the weather. Climatology is not the weather. It is the study of the conditions in which the weather plays out. Krugman is a weatherman.

By attacking physical scientists Krugman shows his territorial markings. He is unwilling to view his own position in a context that is greater than the one he normally deals in. To use Krugman's own logic against him, he is siding with creationists and climate deniers by attacking the knowledge and insights of the physical sciences. Now that he is in bed with these folks, I guess we can fix our attitude against anything he says. Or, we can be reasonable, which is a very scientific thing to be.

Now, some headlines meant to terrify.

BIS warns on "violent" reversal of global markets

All is not well in the Kingdom

A frighteningly real "exogenous" event.

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

Debt Deflation is Us

In the last post on Economic Narratives I made some points I want to clarify and expand on in this post. First of all, I talked about the failure of economics to predict the crisis of 2008 or to recognize the recession which began in January of 2007, with the notable exception of Steve Keen. I asserted that the failure to predict this outcome brought into question the failure of economics as a predictive science. Steve Keen's existence would appear to contradict this, and it certainly does in the case of predicting financial over investment leading to a crisis, but the point of both examples together is to demonstrate how economics gets muddled by assumptions, emotions, and political battles. One of the key features of economics is the "exogenous" event, an event that comes from outside the world economists wish to model. This "exogenous" world outside the models is a very big world.

The larger point I made and will expand on over time is the notion that economic growth has limits. These limits are imposed by laws of nature. If economics is to be legitimized as something useful then it must account for the natural world of hard natural resources limited in quantity and the laws of energy. The economist sees these as peripherals, as simply commodities whose supply to the market is dependent on the demand for them. In other words, natural resources are effectively limitless. It sounds absurd because it is absurd. There will be more on that as well.

For now, some info. These videos are all of Steve Keen. The first is in an interview with Max Keiser and they discuss a lot of things like how capitalism should function, Hyman Minsky instability hypothesis and debt deflation, and why we aren't out of the woods economically.

This video is from a briefing organized by Dennis Kucinich. This was when the "fiscal cliff" was the big debate. Keen warns against driving over the cliff. One of the more interesting parts is when he compares the current crisis to the Great Depression and explains how the wartime economy during World War II fixed the debt overhang created in the 1920's. Note how much government spending was required to finally break the deflation.

Keen is an astute observer and there's plenty that he says which is non-controversial. There's plenty that is, such as his in his remedies, like his idea of a debt jubilee. These two video's do pretty well in setting up the current economic-financial situation for a few current news stories.

Deflation rules the roost

The problem of falling oil prices

Good collection of graphs with some commentary.

A little climate fear.

The larger point I made and will expand on over time is the notion that economic growth has limits. These limits are imposed by laws of nature. If economics is to be legitimized as something useful then it must account for the natural world of hard natural resources limited in quantity and the laws of energy. The economist sees these as peripherals, as simply commodities whose supply to the market is dependent on the demand for them. In other words, natural resources are effectively limitless. It sounds absurd because it is absurd. There will be more on that as well.

For now, some info. These videos are all of Steve Keen. The first is in an interview with Max Keiser and they discuss a lot of things like how capitalism should function, Hyman Minsky instability hypothesis and debt deflation, and why we aren't out of the woods economically.

This video is from a briefing organized by Dennis Kucinich. This was when the "fiscal cliff" was the big debate. Keen warns against driving over the cliff. One of the more interesting parts is when he compares the current crisis to the Great Depression and explains how the wartime economy during World War II fixed the debt overhang created in the 1920's. Note how much government spending was required to finally break the deflation.

Keen is an astute observer and there's plenty that he says which is non-controversial. There's plenty that is, such as his in his remedies, like his idea of a debt jubilee. These two video's do pretty well in setting up the current economic-financial situation for a few current news stories.

Deflation rules the roost

The problem of falling oil prices

Good collection of graphs with some commentary.

A little climate fear.

Friday, October 10, 2014

Economic Narratives

Many of the most powerful narratives in the modern industrial world comes from the thinking on and beliefs about economics as they are made manifest through it's life partner, politics. I named this post "Economic Narratives" rather than "Political Narratives" because looking at economics gets closer to the origin of big ideas that drive politics and, increasingly, causes political activity to grind to a halt. The chain of being follows this course: Economic theory feeds political ideology, which feeds political positions. Political positions on a nationwide basis are, as of this morning, locked into place in some sclerotic and unimaginative pit of history. This is the fruit born from the economic narratives formed over the course of the last century that today have lost their currency, so to speak, here in the early twenty-first century.

The political-economic rhetoric swirling around is familiar enough: No new taxes, tax and spend liberals, government spending is the problem on the right; inequality, wealth distribution, or demand side (usually government) stimulus on the left. I'm not going to get into the merits of these positions. There is a universality to them, after all, and reflect moral or ethical values as much as they reflect real economic thinking. It's the economic thinking used to justify political-economic positions that I question. I'll use two examples to illustrate what I mean.

Back in the summer of 2007 I was listening to an interview with Paul Krugman, nobel prize winning economist and liberal hero. At the time I regarded him as a liberal hero but have come to see him as another misguided economist. In the interview he slammed the Bush economy, which was fine with me, but at the end of the interview he was asked by Minnesota Public Radio's Kerri Miller if the country was headed towards a recession. His answer was 50/50, meaning he did not know whether it was or wasn't going into recession. He did not identify or foresee what, a year and a quarter later, was the bursting of the largest financial bubble in the history of humankind. The recession Miller asked about was later determined to have started in January of that year, six months before the interview.

In the wake of the stock market crash in October of 2008, a very fundamental debate blazed among the market watchers, participant-observers, and opinionators. Call it the Great Inflation/Deflation Death Match and the tangle burst out in response to the negative feedback loop of government market intervention to bail out the banks and subsequent Federal Reserve action involving what's commonly known as Quantitative Easing (QE). The interesting thing about this debate, which has fairly well subsided by now, is that the divide over whether inflation or deflation was the primary concern reflected almost perfectly whether you were a conservative or a liberal. There were some notable exceptions to this, but overall that was the case.

The inflation argument came from the conservative side, especially from the libertarian wing. You'll recall the shrill, panicky predictions that the U.S. would end up like Zimbabwe or Weimar Germany, with folks needing wheelbarrows of money to buy toothpaste. The likes of Glen Beck peddled gold to the faithful so as to protect yourself and your loved ones against the fanatical and reckless policies of the Fed. Even more sober minded folks than Glen Beck believed the inflation story, even the hyperinflation story, warning about the risk the dollar's value would plummet to depths rarely seen in history. As we have seen, the apocalypse didn't come in the form of hyperinflation. At best, the results have been mixed, but deflation has been the primary underlying condition of the economy since 2007.

The deflationists had the better read on the situation. The deficit spending by the government, reached as high as $1.5 trillion dollars at one point, but did not cause inflation. The Fed's QE efforts, which in total has poured around $5 trillion dollars into banks, did nothing to cause inflation, let alone hyperinflation. The screamers from the right clearly missed something here. Why were they so wrong? And will they ever admit they were wrong? They were wrong because the beliefs they subscribe to don't accurately reflect how banking works, the nature of the Fed actions, or the nature of the crisis itself. Ben Bernanke was right not to fear inflation, at least for now.

To be fair, Krugman was not alone in failing to predict the financial meltdown of 2008. Among economists worldwide, there were only ten economists or financial actors on record to have accurately predicted the market crash and for the right reasons. That's out of roughly 30,000 economists around the world who fit the description. Steve Keen, an academic economist out of Australia, won an actual prize for his prediction because his analysis was deemed the most accurate of the ten. He has since railed against the economic models used in academia and everywhere else that matters, pointing out that the reason nobody predicted the biggest market event of our time was because the models everybody (really, everybody) uses cannot predict what happened. He says it's not possible to run the scenario that actually happened using conventional (neoclassical) economic modeling techniques. I find that interesting.

The two examples I used represent two major principles of economics. Inflation and deflation is fundamental to understanding how money operates. The larger concern is the predictive power of economics as a science. Economics is well-known for it's weighing so many complex factors (on the one hand, on the other, and then on the third hand, etc.), that the probabilities almost preclude accurate forecasting. It's the same reason forecasting the weather is so hard. They have to content themselves with being mostly right. C'est la vie. For the weatherman, the weather will at least do something weatherlike. For the economist, economic growth is the weather. The global economy today is on the order of ten times bigger than the global economy of 1950. The assumed natural order is growth, and to contemplate a shrinking economy is to peer into the forest primeval of crap outcomes. It is not in the mind of an economist to consider the possibility that the economy could stop growing, let alone will stop growing, permanently, for reasons they haven't considered simply because it's not in the models.

Growth defines the narrative we have in our collective brains.

The market is down today. Bad news is bad news again for the stock market, apparently. Both Japan and Europe seem to be headed for the "triple dip" recession and this is indeed bad news. Janet Yellen, the new Fed Chief, has taken her foot off the gas peddle of QE and now prices are rising around the world as the dollar strengthens and drives prices lower in America. But this smells like overall deflation. The price of oil is dropping because of demand weakness, breaking through the price floor. The global economy has lingered in a holding pattern of slow growth, gently rising and falling around an uninspiring barely positive rate for about four years now. The previous drivers of global growth, the so-called BRIC's (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) have all slowed considerably. It sure looks like we are entering a new worldwide recession, and we have many fewer bullets, financially speaking, to try to kill it.

This could be the stirrings of a phase change in the ongoing march of the global economy. The swings are widening, foretelling a destabilized financial environment (remember the debt). And there's nothing markets hate more than a destabilized financial environment.

Here are some pertinent links.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-10-09/ceos-tout-reserves-of-oil-gas-revealed-to-be-less-to-sec.html

http://www.cnbc.com/id/102076504

http://www.cnbc.com/id/102073512

The political-economic rhetoric swirling around is familiar enough: No new taxes, tax and spend liberals, government spending is the problem on the right; inequality, wealth distribution, or demand side (usually government) stimulus on the left. I'm not going to get into the merits of these positions. There is a universality to them, after all, and reflect moral or ethical values as much as they reflect real economic thinking. It's the economic thinking used to justify political-economic positions that I question. I'll use two examples to illustrate what I mean.

Back in the summer of 2007 I was listening to an interview with Paul Krugman, nobel prize winning economist and liberal hero. At the time I regarded him as a liberal hero but have come to see him as another misguided economist. In the interview he slammed the Bush economy, which was fine with me, but at the end of the interview he was asked by Minnesota Public Radio's Kerri Miller if the country was headed towards a recession. His answer was 50/50, meaning he did not know whether it was or wasn't going into recession. He did not identify or foresee what, a year and a quarter later, was the bursting of the largest financial bubble in the history of humankind. The recession Miller asked about was later determined to have started in January of that year, six months before the interview.

In the wake of the stock market crash in October of 2008, a very fundamental debate blazed among the market watchers, participant-observers, and opinionators. Call it the Great Inflation/Deflation Death Match and the tangle burst out in response to the negative feedback loop of government market intervention to bail out the banks and subsequent Federal Reserve action involving what's commonly known as Quantitative Easing (QE). The interesting thing about this debate, which has fairly well subsided by now, is that the divide over whether inflation or deflation was the primary concern reflected almost perfectly whether you were a conservative or a liberal. There were some notable exceptions to this, but overall that was the case.

The inflation argument came from the conservative side, especially from the libertarian wing. You'll recall the shrill, panicky predictions that the U.S. would end up like Zimbabwe or Weimar Germany, with folks needing wheelbarrows of money to buy toothpaste. The likes of Glen Beck peddled gold to the faithful so as to protect yourself and your loved ones against the fanatical and reckless policies of the Fed. Even more sober minded folks than Glen Beck believed the inflation story, even the hyperinflation story, warning about the risk the dollar's value would plummet to depths rarely seen in history. As we have seen, the apocalypse didn't come in the form of hyperinflation. At best, the results have been mixed, but deflation has been the primary underlying condition of the economy since 2007.