In the URL of this blog resides the word "decomplexity". It is not a real word, but I invented it out of the wish to have a single unused address for the blog that would be, or could be, made sensible. Decomplexity refers to a future state society, or civilization, will inevitably reach given natural resource constraints to it's continued existence. I say "inevitable" because I mean inevitable. By saying that, however, doesn't mean the power to achieve or to choose certain outcomes isn't possible, but we have to choose carefully among these limited options. Further investment in complexity further constrains our options over time, so choices made now have huge implications later.

In any given system, the level of complexity of that system is determined by the amount of available energy to that system. An ecosystem has a high or low level of biodiversity based on the energy flows going through it. The same holds true for complex machines, organisms, or socio-economic organizations. A cell phone is a complex machine. In itself it uses relatively little energy to operate, but is useless without a system of server farms, cell phone towers, manufacturing plants, and millions of consumers to pay into the system. This system which enables a cell phone to function uses more energy than the system it replaced, namely the old land line phone system. The increase of energy translates into greater GDP for the economy.

The system on which cell phones depend represents a greater complexity for society as a whole. Technology as a whole adds complexity and by extension adds costs. Technology adds efficiency, but efficiency itself comes at a cost. The only way to overcome these costs is by adding energy to the system, namely the economic system, which is the way the system is measured. By following the flows of money you can get a picture of the systems complexity.

In 1987, to little fanfare, a book called "The Collapse of Complex Societies" was published. It was written by the archeologist Joseph Tainter pursuing the age old question of why civilizations collapse. He was looking for a cause which unified all cases of civilization collapse seeing the ongoing theories at the time as inadequate for explaining every case. He goes through an exhaustive review of all the theories at the beginning of the book and provides counter examples to disprove a multitude of theories. What he found to unify every instance of collapse was what looked like the economics "Law of Diminishing Returns".

The diminishing returns he saw was in the response to crises of various sorts that a civilization confronted by adding complexity to it's systems. This applied no matter the scale of the civilization. From Rome to the Chacoan of the American southwest, a tiny society numbering maybe ten thousand at it's peak, the story was the same. He found in the archeological record the course of crises and the responses to them a pattern of adding more complex structures, which made things more efficient, but also added greater energetic and maintenance costs. At this point, things should start to sound familiar. Eventually the costs outweighed the benefits, which made the society less resilient to further crises and susceptible to collapse.

John Michael Greer has a spin-off theory of "Catabolic" collapse which describes the forces that eat away at the resilience of the society on it's way down.

How does this apply to the current situation of global civilization? What signs are there of diminishing returns? I will look at the trends in energy and debt to make my case.

We are getting diminishing returns on the amount of debt needed to get a unit of GDP growth. You can see how the crisis of 2008 could be devastating. If the debt line drops you are in a deflationary trap.

Now, in conventional economic theory, the price is the product of supply and demand. This holds true for oil even with today's high prices. A rising price means demand is outstripping supply and the market should, according to theory, respond with greater supply to the market. But this is not happening, as this chart makes clear.

This next chart shows the history of real and nominal oil prices over the entire history of the oil industry.

Compare this to the first chart and notice that, in the first chart, the debt line began to diverge from the GDP line in the early 1970's. This third chart shows that the price of oil got all wonky at the same time. The reason why this happened doesn't matter, the only point necessary to make is that these two events went hand in hand.

And now a look at total debt as a percentage of GDP.

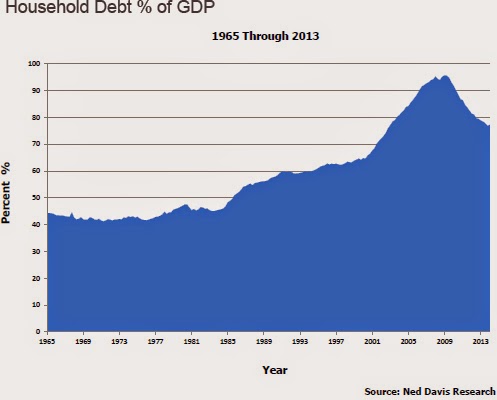

Total debt includes both public (government) debt and private (household and corporate) debt. Most of this debt is not from government. It is from the private sector. Government debt as a percentage of GDP is on the rise now because private sector debt, mainly household, is falling. The reason the Federal Reserve has been pushing down interest rates is to spur further borrowing by the private sector. Here's a picture of household debt.

This is the profile of household deleveraging (paying down debt). It is the same process that characterized the Great Depression.

This collection of graphs tells the story of diminishing returns. Another way to put it is that the costs of maintaining and growing the system is outstripping the benefits. Our answer to these trends has been to increase complexity and efficiency, through debt accumulation, in the hope that the economy will "break out" of it's doldrums and start another virtuous cycle of growth. Growth in the economy is imperative to service the outstanding debt. Global growth rates have been flat and we appear to be entering a new crisis period because of the pressure to delever. How should we respond? Should we add more debt to try to spur more growth? The answer is not as straightforward as it seems.

Before anything major gets decided on people should at least acknowledge our predicament, but we're far from doing that. Accepting the end of growth story and all of it's implications is indeed depressing and/or frightening and most everyone resists even considering the possibility. But that has to be gotten through when the time comes to respond in an intelligent and thoughtful way when this system of economy chugs to it's final failure. I don't know when that will be and nobody can say exactly when. But given the condition of the world right now, it's possible to see the shape that failure will take, and it looks like a prolonged economic depression that we can only adapt to and make the best of. But to expect economic growth to return in any meaningful way is pure folly.

Today's links on deflation:

Bond Markets Respond to Deflation Fears

The Feds response seems to be:

Fed

Our friends at the House of Saud don't appreciate our shale oil "revolution":

Loyal Allies

2 comments:

“How should we respond? Should we add more debt to try to spur more growth? The answer is not as straightforward as it seems.”

I think we will add more debt as the upcoming recession/depression will become too painful. Of all the purposes for big new debt I suppose I’d be most amenable to big energy investment. But the payoff will come over the coming decades and the costs will be borne now. So I don’t see how that gets done either. Some kind of partial debt jubilee might be inevitable, but that will certainly stunt credit availability and investment for many years to come. I suppose my ideal would be targeted social simplification i.e. lower spending on some areas of government budget combined with greater concern for inequality by taxing higher incomes. Current spending could be partially diverted to pay for massive renewable investment. Of course, this combination of flat to declining spending and higher taxes would hurt the economy. But the alternative of ever-increasing debt and inequality will probably create a society so brittle that political extremism and violence could greatly hasten the process of catabolic collapse….. whew! So much to think on here…sorry for the rambling but a few of my thoughts anyway…

The quality of the debt we would take on now depends on how effectively it allows the future to pay it off. In that sense, given the nature of physical limits, any debt we take on now will be too expensive to pay off. Investment in renewable energy is bound to have the most pay-off. I think the mentality of our contemporaries makes some sort of financial crash inevitable, at which point governments will be forced to take on the bulk of investment. A WWII style Keynesian economy would be the logical choice. Of course, many in the U.S. would resist that mightily, but other countries don't have the ideological prohibiters to that course of action the U.S. has.

Post a Comment